The Original Bambi: The Story of a Life in the Forest

Felix Salten, translated by Jack Zipes, with illustrations by Alenka Sottler

Princeton University Press

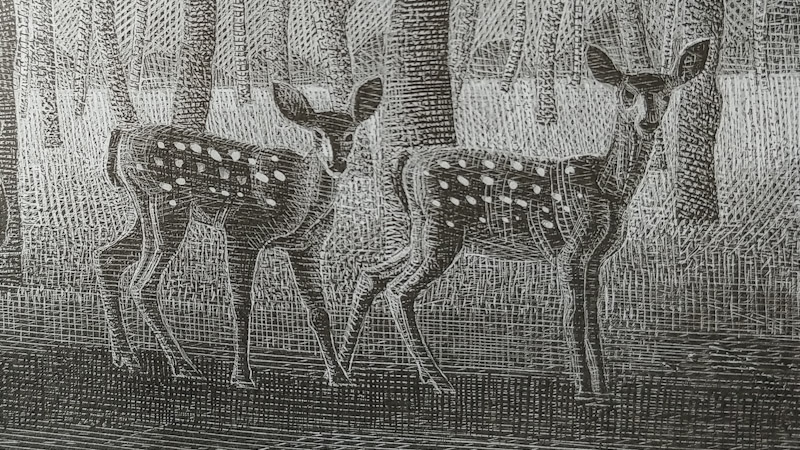

“Two leaves fell from the great oak tree at the edge of the meadow.” Thus begins the eighth chapter of Felix Salten’s 1923 nature parable Bambi: The Story of a Life in the Forest, just published in a new English translation by Jack Zipes from Princeton University Press, with evocative illustrations by Alenka Sottler. There can be few things as insignificant in the forest as the ephemeral fate of two leaves, among the millions which fall every autumn. Yet, Salten offers a brief caesura at the virtual midpoint of the book to consider their fates.

“Two leaves fell from the great oak tree at the edge of the meadow.” Thus begins the eighth chapter of Felix Salten’s 1923 nature parable Bambi: The Story of a Life in the Forest, just published in a new English translation by Jack Zipes from Princeton University Press, with evocative illustrations by Alenka Sottler. There can be few things as insignificant in the forest as the ephemeral fate of two leaves, among the millions which fall every autumn. Yet, Salten offers a brief caesura at the virtual midpoint of the book to consider their fates.

“It’s not like the old days… No one knows who’s going to fall next,” one leaf says to the other just before the end. They ponder what lies ahead – the great mystery of death that awaits on the forest floor. “What happens to us when we fall from the tree?” the second leaf asks. “Who knows?” the first leaf replies, “None of those who have fallen down there have ever returned to tell us about it.”

Amid the fear of their final moments, the first leaf exhorts its neighbor to “remember now just how beautiful it was, how wonderfully beautiful, when the sun came and glistened so hot that we thought we’d burst with health. Do you still remember? And the morning dew and the mild glorious nights?” But those days are long past. “Now the nights are terrible… And there’s also no end to them,” the other leaf replies.

The short scene is absolutely critical to Salten’s narrative, but if your only exposure to Bambi is the 1942 Walt Disney animated feature film, you would never have heard of it. Even the English translation by Whittaker Chambers, on which the movie was very loosely based, subtly reconfigures the episode by gendering the leaves. For Chambers, and for the millions of readers who have read his translation since it was published in 1928, it is a meditation on the brevity of feminine youth and beauty.

In the original German – a highly gendered language, no less – the leaves are neutral; they are just leaves. Yet their dialogue, full of a sense of loss and dark portents of the future, speaks to something deeper, more universal, and more tragic, and the new translation reveals those themes and restores the chapter, at two-and-a-half pages the shortest in book, to its position of narrative centrality.

Salten’s Bambi is no children’s story, as Zipes notes in his introduction to Bambi: The Story of a Life in the Forest, and the dialogue of the leaves is the fulcrum between the first half of the narrative, a woodland bildungsroman focusing on Bambi’s discoveries and his accumulation of knowledge and confidence as a “young prince” of the forest, and the second half, which is a story of violence, terror, and tragedy. There is no Thumper and Flower in this tale, only betrayal, death… and the ominous presence of “man,” his lackeys, and his gun.

Felix Salten was born in Pest in 1869, and moved as an infant to Vienna with his mother and father, the son of a Hungarian rabbi. For central European Jews in the late-19th century, Vienna was a virtual paradise of freedom and possibilities. Legally emancipated in 1867, Austrian Jews could, for the first time, freely attend the empire’s universities, serve in the military and civil service, hold any occupation, and even vote. The growing Viennese Jewish middle class would remember the three decades that followed as a kind of golden age.

“Their desire for a homeland, for peace, repose, and security, a place where they would not be strangers, impelled them to form a passionate attachment to the culture around them,” Stefan Zweig would recall shortly before his death in 1942. “And nowhere else, except for Spain in the fifteenth century, were such bonds more happily and productively forged than in Austria.”

A generation of Jewish burghers thrived in fin-de-siècle Vienna’s congenial, liberal atmosphere, and produced the luminaries of late-19th and early-20th century European arts, letters, and scholarship. They included Zweig (born in 1881), Arnold Schoenberg (1874), and Martin Buber (1878); many others born in other parts of the Hapsburg Empire and the German-speaking world, made their names in the Austrian capital. Sigmund Freud, born in Freiberg, Moravia in 1856, came with his family in 1860, just before emancipation.

The literary Bohemians who congregated at the Café Griensteidl and who sought to revolutionize German-language literature were disproportionately Jewish – Zweig, Arthur Schnitzler, Peter Altenberg, Richard Beer-Hoffmann among them. Some, like the novelist Jakob Wassermann, who was born in the Bavarian town of Fürth, came from further afield, but Vienna was their home. And they were collectively Jung Wien, “young Vienna,” forever associated with the city on the banks of the Danube.

Dropping out of school, Salten fell-in with Jung Wien, first making his name as a journalist covering Vienna’s flourishing, and often scandalous, theater scene. Like so many of his Jewish colleagues, he worked hard to assimilate to literary Vienna, changing his name from the decidedly-Jewish Siegmund Salzmann and, like his contemporary Zweig, affecting the manners and style of a Central European aristocrat, whether or not he could actually afford it.

Salten seemed to fit-in well with the Vienna literati and their blue-blooded patrons; his silk ties, starched collars, and neatly-trimmed moustache betrayed nothing of Siegmund Saltzmann from Pest. And he enjoyed considerable success as a gossipy journalist, serious essayist, and writer of short fiction. His pornographic novel Josefine Mutzenbacher, published anonymously in 1906, was both a succès de scandale and a runaway bestseller; it was banned in Austria from 1913 until 1971, though available elsewhere – and in dozens of translations.

But the golden age of Jewish Vienna could not last. By the end of the 1890s, Viennese politics took a populist turn, bringing Karl Lueger to the office of mayor on an explicitly antisemitic platform in 1897. Lueger would remain in office until 1910 and, even though Zweig was inclined to excuse him from the perspective of 1942 – “he never stepped beyond the bounds of decency, and while he had his equivalent of Julius Streicher, he kept him carefully under control” – things had certainly changed for Vienna’s Jews.

The popularity of Lueger and his Christlichsoziale Partei (Christian Social Party) was rooted in widespread antisemitic agitation that followed the apparent murder of a Christian girl in the Hungarian town of Tiszaeszlár in 1882. More than a dozen of the town’s Jewish community were accused of Eszter Solymosi’s ritual murder, and when they were acquitted, antisemitic riots swept through Hungary. Seventeen years later, a Czech Jew named Leopold Hilsner was convicted of the ritual murder of another Christian girl on virtually no evidence. The Austrian Crown acknowledged that Hilsner had been the victim of a blood libel, and pardoned him. But a great many Christian subjects of the Hapsburg empire were convinced that the Jews were getting away with murder.

A new kind of antisemitism was rising throughout the Empire and even Zweig, at 20 already dedicated to assimilation, took notice. “Im Schnee” (“In the Snow”), one of his first stories published in 1901, evokes an anxiety that would never go away. The story tells of a prosperous Jewish community in “a small medieval German town close to the Polish border” waiting helplessly for the murderous pogrom that they know will come. “Can a Jew defend himself or fight back?” Zweig writes. “As they see it the idea is ridiculous, unimaginable; they are not living at the time of the Maccabaeans now, they are enslaved again.”

The Jews ultimately choose to flee en-masse, only to get caught in a blizzard. They die together, as a community, under the irresistible power of nature. Soon, it will be spring, Zweig writes, “bringing buds and green leaves back again, and will lift the white shrouds from the grave of the poor, lost, frozen Jews who have never known true spring in their lives.”

If antisemitism was a menacing presence before 1914, it had become and explicit danger in the years after 1918, when the Hapsburg empire lay shattered and dismembered, and the humiliated German Reich bled hyperinflation and unemployment. Joseph Roth reported in 1924 on the trial of Adolph Hitler and his accomplices for their part in the Beerhall Putsch for the Socialist newspaper Vorwarts. “The tombs of world history are yawning open in Munich and all the corpses once thought interred are stepping out,” he wrote with a palpable shudder. “A grotesque dream is forming and all Germany accepts this miracle with indifference, as if it was self-evident.”

Political antisemitism, now given form in mass movements like Austria’s Fatherland Front, the Arrow Cross Party in Hungary, and Hitler’s National Socialist German Workers Party, was marching in hobnailed boots across Europe, stopping only to brawl with the Communists. The “grotesque dream” was a shared nightmare for European Jews, and seemed, Zweig would note, to be moving inexorably to a climax.

One could not be Jewish in Vienna, or Berlin, or anywhere else in the German-speaking world without being conscious of a stinging antisemitism that marked the Jews – even those like Salten who tried so diligently to assimilate – as unwelcomed outsiders. “I am a German and I am a Jew, one as fully as the other, neither can be disconnected from the other,” Wassermann insisted in his 1921 autobiography Mein Weg als Deutscher und Jude (My Life as German and Jew). Yet, he noted that his whole life consisted of justifying the legitimacy of his Germanness to gentile Germans – and it was getting harder to do.

“It is futile to beseech the nation of poets and thinkers in the name of its poets and thinkers,” he wrote. “Every prejudice that one believes to have been shrugged off brings one thousand new ones to light as a carcass does worms.”

Zweig’s 1929 short story “Buchmendel” (“Mendel the Bibliophile”) neatly evoked the plight of Central Europe’s Jews, for whom emancipation had promised so much. The decades before the Great War had been, for them, a time when, as Salten’s leaves reflect, “the sun came and glistened so hot that we thought we’d burst with health.” It was a time when Zweig’s Jakob Mendel held court “in the Café Gluck at the upper end of the Albertstrasse” in Vienna. Revered for his uncanny knowledge of books, Mendel was a central figure in Vienna’s literary scene.

“Mendel was as much a part of the fixtures and fittings as the old cherrywood cash desk… and his table was protected like a shrine…” Yet, with the coming of the war, he is exposed as a foreigner, arrested and, despite his protests “in sing-song Jewish tones,” remanded by the Austrian authorities to a concentration camp. After the war, his mind and spirit “destroyed beyond redemption,” Mendel is unable to return to his place of prominence among the Viennese literati and, when Zweig’s narrator stumbles across the Café Gluck a decade later, he is the ghost of a forgotten past.

This sense of loss and betrayal, and the growing anxiety about what it might mean for Jews like Salten – and Zweig, Wassermann, and Roth – pervades every page of Bambi. Even in the first half of the book, as the “young prince” of the forest explores his world in wide-eyed wonder, and frolics in the meadow with Faline before the first stirrings of maturity, there is always the figure of “man” looming in the shadows.

One of the first lessons that Bambi’s mother teaches her fawn is to be wary of man. “We have to live this way,” she tells him early in the book. “All of us. Even if we love daylight – and we love daytime especially in our childhood – we must live this way and be on the alert whenever we move about.” Some pages later, Bambi catches a glimpse of the threat: “A terrifying dread emanated from this face. Cold horror. This face had a tremendous power that could cripple anyone.”

In the latter half of Bambi, after the leaves offer their sad benediction on the lost, bright days of promise, the extent of the control that man exerts over the social environment of the forest becomes clear. More than any other force, man has the power over life and death; it is his (“man” is gendered masculine) hand that brings death and slaughter. A great hunt litters the ground with the carcasses of forest animals and, although the “young prince” escapes, both Faline’s brother Gobo and Bambi’s mother disappear. It is the most traumatic scene in the Disney film but, in the book, it is only the beginning.

Gobo returns alive a few chapters later. Man did not kill him, but carried him away to his home and kept him as a pet. Faline’s brother explains to the assembled woodland creatures that man is both immensely powerful and misunderstood. “You all think He’s evil,” Gobbo tells them. “But He isn’t evil. If He loves someone, or if someone serves Him, he’s good to him. Wonderfully good!” Animals have nothing to fear of man, as long as they play by his rules, Gobo says, and he proudly wears a collar as a badge of his assimilation to the human world. “It’s His collar, and it is the greatest honor to wear His collar.

Man returns to the forest a few pages later, and Gobo strides out into the exposed meadow, despite the other animals’ warnings. “Danger! Danger! Who cares about that? Not me… If He’s there, I want to greet Him.” Yet, in the forest, there are no pet deer, only prey. A shot rings out and, with “his bloody entrails streaming from his torn flank,” Gobo comes to the tragic realization that “He doesn’t recognize me.” The hunter bends over and grabs “the wounded Gobo. Then they heard Gobo’s wailing death shriek.”

For a generation of European Jews who had been completely committed to assimilating to Germanic kultur, the scene is a chilling warning that foreshadows a terrifying future sixteen years before Kristallnacht. No matter how tame, a deer is still a deer, to be shot and gutted for the dinner table; no matter how assimilated and refined, to the Central European gentile world, a Jew will always be a Jew.

When the conflagration finally came, and the Brownshirts threw their great contributions to kultur on the pyre in a dress-rehearsal of the Holocaust, the Jewish writers and poets of Young Vienna, and other artists and intellectuals just like them, German and Jewish “one as fully as the other,” escaped like the animals of the forest before the hunters. “Finally, [Bambi] felt he could unleash his pent-up desire to get away from the tumult and far from His scent.”

Zweig, like Freud, made his way to Britain, and then onward to South America. Roth set out for Paris, along with many others, like Walter Benjamin, who resolved until the last moments of his life to be the “last European.” Salten fled to Zurich after the Anschluss in 1938 and died there mere weeks after the end of the Second World War. He never saw the animated film of his novel, for which he was paid $1,000.

Those who only know the story of Bambi from that film, remember a heartwarming tale of a precocious fawn, his rabbit and skunk pals, of young love, and the tragic loss of a loving mother. Even readers who came to the story through Chambers’ translation may only remember what John Galsworthy called, in the forward to the first English edition, “a delicious book” by a “poet” who “feels nature deeply, and… loves animals.”

Restored and revealed in this new translation, Bambi is truly neither of these things. It is a document of terror and impending peril, a warning by an outsider who devoted his life to fitting in, and to the generation who believed the promise of emancipation, that they would always be outsiders – under the menacing shadow of violence, and hunted for sport. It is a warning from a dark time that perhaps bears heeding today.

***

Image: A detail of one of Alenka Sottler’s illustrations.