I am not an optimist by inclination. I was raised Jewish in the 1960s and 1970s, and learned about the full enormity of the Shoah from people who experienced it. There were Nella Lacks, and Mr. Preisler at summer camp, who had the numbers on their arms; so did Mr. Kastner at the bar-and-grill at the YMHA in Snowdon and so did the parents of some of my friends at Hebrew school. The lesson that I took from that is that humans can be extraordinary cruel to each other, and that there is often very little that we can do to stop them – especially when they act in numbers.

When I was a journalist, part of my beat was the neo-Nazi and white nationalist movement which gained momentum in the 1980s and 1990s. I interviewed people like Ernst Zundel, and William Pierce’s protege Milton John Kleim, then known as “Net Nazi Number One.” I read The Turner Diaries, the rantings of Richard Girnt Butler and Tom Metzger, and a cache of documents from the Covenant the Sword and the Arm of the Lord, retrieved from Elohim City. I sat with the widow of a victim of white nationalist terrorism and watched her weep as she described the night her husband was murdered. I could do nothing for her.

Throughout the 1990s, in the early days of the Internet, I worked with anti-Nazis at the Simon Wiesenthal Center and the Nizkor Project, and was even honored by the B’Nai Brith League of Human Rights for my efforts. Yet, time has worn on, and the Nazis remain, even more numerous and aggressive than before, and with a growing mystique among the totalitarian masses and even-deeper roots in the mainstream political right, I can’t shake the sense of impotence that I felt sitting with the grieving widow.

Perhaps it was that sense of futility about the journalist’s trade that inspired me to become a historian. I remember speaking with a senior mentor and saying that one of the things that attracted me to history is that, in the longue durée, at least one can see change. There is, I confidently pronounced, a sense of hope that things can improve, if only one can see the workings of grand historical processes. I was committed, at the time, to a kind of messianic Marxist historiography, and I really believed that the revolutionary apocalypse lay at the end of history.

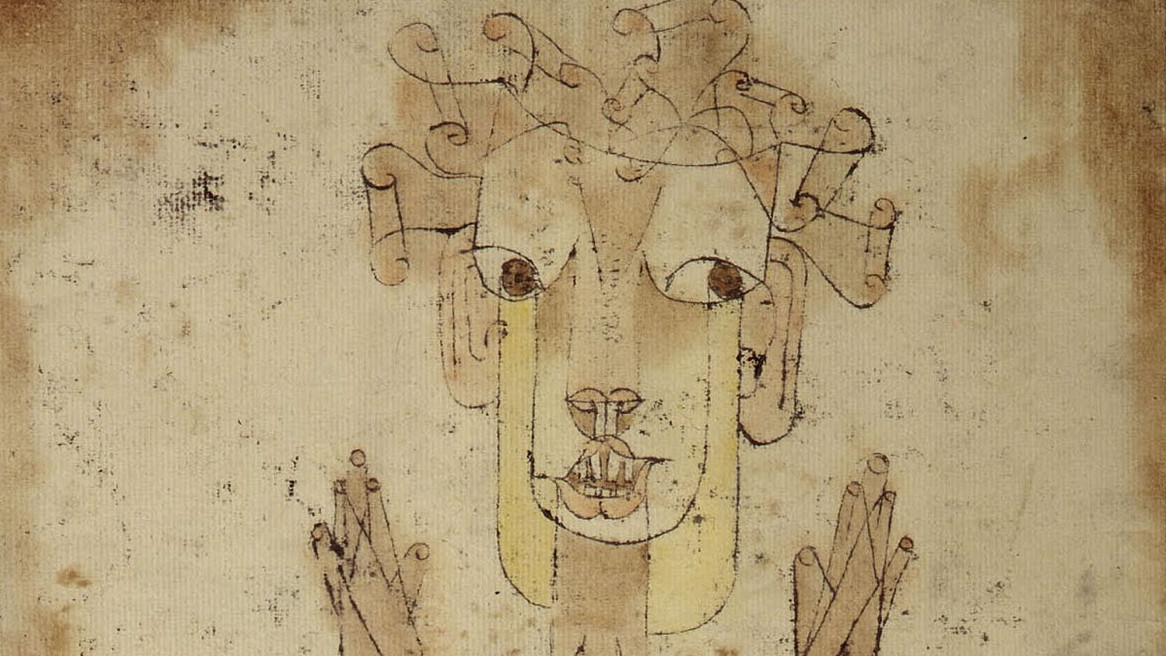

There are vast historical processes but I have begun to realize that, as Marx himself noted, they unfold behind our backs. For all of our messianic optimism, we really don’t know which way things will go, we can only observe what they have produced. I find myself nodding at what Walter Benjamin wrote about the Angel of History who walks backward into the future and “sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet.” History is blind to the future, and its vast processes are like icebergs, driven by forces beyond our full comprehension, and maintained by inertia.

The wreckage is overwhelming, and it piles up despite our best efforts.

I remember feeling a surge of confidence that the culture wars had been won when I celebrated the Supreme Court’s recognition of marriage equality just seven years ago. Yet, the conflict only escalated as the totalitarian masses, stung and inspired by the defeat, found their political voice, mobilized, and mounted a flanking operation on women, LGBT people, BIPOCs, non-Christians, and everyone else they believe is, or should be excluded from the body politic.

In my work as a historian and journalist, I have had to dig deep into Christian nationalism, Dominion Theology, or whatever you want to call it, reading about how “Christians have an obligation, a mandate, a commission, a holy responsibility to reclaim the land for Jesus Christ – to have dominion in the civil structures, just as in every other aspect of life and godliness. But it is dominion that we are after. Not just a voice.” Far from being a text from the lunatic fringe, this was the program proposed by the mainstream Presbyterian pastor George Grant in his 1987 handbook for Christian political activism Changing of the Guard: Biblical Blueprints for Political Action. Grant is still a minister and, if anything, even more prominent today than he was 35 years ago.

There seemed to be momentum for an expansion of human rights after Obergefell v. Hodges, and Roe v. Wade seemed so entrenched in settled law that, even just a few years ago, no one seriously imagined that it would be overturned. Congress passed an assault weapon ban in 1994 with bipartisan support – even the conservative hero Ronald Reagan spoke in its favor.

Yet, here we are, with Christian nationalists instead banning the very mention of anything relating to non-traditional families in schools and prohibiting the teaching of anything that might make white people feel bad about their history. The long-cherished right of a person’s bodily autonomy, and all the implications that it has for reproductive justice is about to wiped away and, with a young, Christian nationalist – nay, Christian chauvinist – supermajority on the Supreme Court, we know that it is only a matter of time before other “settled law” follows.

As for the ban on assault weapons for which former President Reagan advocated as the eminence grise of American conservatism, it expired in 2004, eight years before Sandy Hook and fourteen years before Parkland. I need only write the names of the towns where so many young people have died, and we all feel the weight of the enormity. Today, there are more guns – as many as 400 million in America –and more assault weapons, which are more easily obtained and even less restricted than ever. All of the death has not changed that one whit, in fact, and things only seem likely to get worse.

Whither the processes of history? I might cleave to something like the evolutionary theory Stephen Jay Gould and Niles Eldredge called “punctuated equilibrium,” but repurposed for political economy: history remains stable and unchanging until interrupted by some transformative crisis, and then… and then… Biological metaphors rarely map well over history and what we are witnessing is not crises that bring change, but crises that bring no change at all. There might be bumps along the way, as in 1973 or 1994 or 2015, but the equilibrium of oppression, violence, and hate invariably smooth them out.

One could make an argument, then, for what George Orwell called catastrophic gradualism: “History necessarily proceeds by calamities, but each succeeding age will be as bad, or nearly as bad, as the last.” Such a notion, however, seems both defeatist and self-justifying. “The formula usually employed is ‘You can’t make an omelette without breaking eggs,’” Orwell observed. “And if one replies, ‘Yes, but where is the omelette?’, the answer is likely to be: ‘Oh well, you can’t expect everything to happen all in a moment.’”

Catastrophic gradualism demands a kind of omniscient perspective that an evolutionary biologist might have of their fossils, but which the Angel of History denies us as it strides backward into the future. Indeed, Orwell’s (and Arthur Koestler’s) Utopian faith that some kind of “change of heart” among individuals-as-a-mass can inaugurate real historical transformation is based on the same misguided presumption of the infinite capacity of human reason and knowledge.

That is what makes it so Utopian yet, if the Second Law of Thermodynamics, Werner Heisenberg, and the incomprehensible chaos around us tell us anything, we can know nothing with any certainty about our historical moment, let alone about the future, or how to achieve it.

So, in the aftermath of Buffalo and Uvalde, anticipating the likelihood of the Supreme Court’s final decision on Roe v. Wade, and fearing all that will come in its wake, I am not optimistic. Nor, at the same time, am I resigned to passively accept the horrors that will come. I might not be able to stop it, but I will not accept the inevitability of a future that I cannot possibly know but merely hope to divine from the wreckage strewn in history’s wake.

What is left is resistance. More than Orwell’s Utopian “change of heart,” I find myself recalling how Hannah Arendt noted the isolated, ultimately ineffectual resistance of a German sergeant named Anton Schmidt to the Shoah. The story was “like a sudden burst of light in the midst of impenetrable, unfathomable darkness,” she wrote, “a single thought stood out clearly, irrefutably, beyond question – how utterly different everything would be today… if only more such stories could have been told.”

This is a prescription for ethical action. The impersonal forces of history, like the totalitarian terror of Nazi Germany, are overwhelming, standing against them is hard and very likely futile, and “most people will comply but some people will not.” And that reality makes resistance an ethical act; one can either accept the near inevitability of a future replete with horrors equal to and exceeding those of the present and go along, or recognize it and resist it anyway.

When I think of Nella Lacks, Mr. Preisler, Mr. Kastner, and all the other survivors of the Shoah whose stories evacuated my youthful optimism for humanity and its future, I reflect that they did survive. Their survival, however they accomplished it, is a rebuke to the forces that would have destroyed them and a resistance to the blind processes of history. The historian Yehuda Bauer wrote in Rethinking the Holocaust about the manifold forms that resistance to the Holocaust took, and settled on Amidah, the name of a sequence of prayers that Jews recite while standing.

“In this context it means literally ‘standing up against,’ but that does not capture the deeper sense of the word,” he wrote. What he meant was that “standing up against,” offering a resistance, no matter how futile, “sanctified life” as does the prayer. Use whatever word you must if “sanctified” does not suit your taste – respect, honor, glorify all work as well – but that is the ethical vocation. One need not believe that success is possible, or even likely. But one must stand up against.

As Audie Wood wrote earlier this week: “The road ahead looks bleak, but the fight is not going to go away.” Nor should we.