I laughed so hard that I passed beer through my nose. The occasion was the first episode of Saturday Night Live’s 14th season which aired just days after the High Holy Days in 1988. Hosted by Tom Hanks, whose movie Big had been a surprise summer blockbuster, with the hit-or-miss third version of the Not Ready for Prime Time Players, the episode featured one of the most trenchant gameshow parodies in the long-running series’ history.

“Jew, Not a Jew” found Hanks, as host Bob Tompkins, pitching questions to two painfully white-bread couples, the Scandinavian-American Knutsens, played by Kevin Nealon and Victoria Jackson, and the generic WASP Johnsons, played by Phil Hartman and Jan Hooks. “The game that all Americans love to play,” is simple enough; host Tompkins shows the contestants the picture of a celebrity, and they say whether the celebrity is a Jew, or “not a Jew.”

It was a delicious satire that set up how Christian America traffics in antisemitic stereotypes. Presented with a photo of Penny Marshall, the actress who played Laverne with broad slapstick on Laverne & Shirley, and who had just directed Hanks’s star vehicle Big, the Knutsens confer as the timer ticks down. “I think she’s from Brooklyn somewhere,” whispers Nealon’s Greg. “Okay, okay,” Jackson’s Debra finally answers, “we’re gonna go with Jew, Bob!”

Sadly, the Knutsen’s miss the mark, and Bob explains, “Ohhh! No, I’m sorry, Penny Marshall was born Penelope Mashirelli, she is an Italian Catholic. Italian Catholic!”

The joke was, of course, utterly tasteless, and it made my skin crawl – but that was also what made it hilarious, a very dark satire, and why I snorted my Molson in the general direction of the TV. To be a Jew in North America is to encounter this kind assumption on a frighteningly regular basis. If they’re a rich entrepreneur with a vaguely-Germanic name, they must be a Jew; if they’re a public intellectual who advocates for progressive public policies, they must be a Jew; if she’s funny and ethnic, and has a Brooklyn accent, she must be a Jew.

If they’re a vaguely-threatening, slightly swarthy outsider with curly hair, or a prominent nose, or arriviste authority based on an “East Coast” college education, or they don’t conform to conventional (Gentile) gender norms, or they’re “loud,” or “pushy,” and somehow unlikeable, then they must be a Jew. We are so conscious of these antisemitic stereotypes, even when they are couched as backhanded compliments (“you people are so clever/funny/great at business”), that many of us go through phases in our lives trying to pass as anything other than a Jew… Just to be yourself, rather than an ethnographic type.

The antisemitic compulsion to assign Jewish identity to any suspect other – and to thus mark all Jews as suspect others – is always annoying and often deeply offensive. Yet, what I found so biting about the “Jew, Not a Jew” sketch’s satire was the frisson of recognition that we often do just the same thing, to ourselves.

For minoritized communities like ours, discovering “one of our own” in a position of prominence, authority, or pop culture celebrity brings a powerful sense of pride and, to be honest, relief. I remember my parents sighing with satisfaction when Sammy Davis, jr. closed a television variety special raising a wine glass and saying “l’chaim” right into the camera. Despite their differences – he was a Nixon supporter at the time, and my parents most certainly were not – Davis was a proud, open, and very public Jew, and that was something to celebrate.

I felt the same kind of thrill when I learned that William Shatner – Star Trek’s Captain James T. Kirk – was Jewish; not only that, he grew up Jewish in my hometown of Montreal, and not only that, my father knew him from Camp B’Nai Brith, when the soon-to-be-captain was a counselor-in-training, and my dad was (get this) his boss. Every Montreal Jewish family has a similar connection to Shatner, and our collective and shared relationship to one of the biggest stars in the galaxy is one of the main sources of our local community’s cohesion. That, and bagels.

To be honest, though, I was much more excited to learn that Leonard Nimoy was Jewish; there was something about his Mr. Spock that seemed to validate a certain kind of cerebral Jewish masculinity (and he kind of looked like my cousin Ralph). The fact that Walter Koenig, who played Chekov was Jewish was just sour cream on the blintz. It almost didn’t really matter that James Doohan (Scotty), who wasn’t Jewish, was Canadian.

Let’s face it: Representation matters. It can be profoundly validating for minoritized others to see the mere presence of members of our communities in the public eye, even performing heroic roles in popular media. “Look! They’re one of us! We can be heroes, leaders, artistic geniuses, too!” Often enough, our heroes recognize this, too, and make a point of standing up for their communities to provide a visibility that interpellates us into a kind of cultural citizenship only grudgingly granted by the Knutsens and Johnsons.

That is all well-and-good; generations of Jews have taken great pride in knowing that they not only have Jewishness in common with great intellectuals like Albert Einstein, Jonas Salk, and Sigmund Freud – giving rise, unfortunately, to the myth of der Yiddisher kop – but also with Paul Newman, Mila Kunis, and David Duchovny, Sandy Koufax, and Dara Torres. But, it never stopped there: The understandable desire to find a connection with fellow Jews wherever they might be in the worlds of high and low culture, sports, and arts and letters can morph into a compulsion to write Jews into places where they are not and to rewrite history.

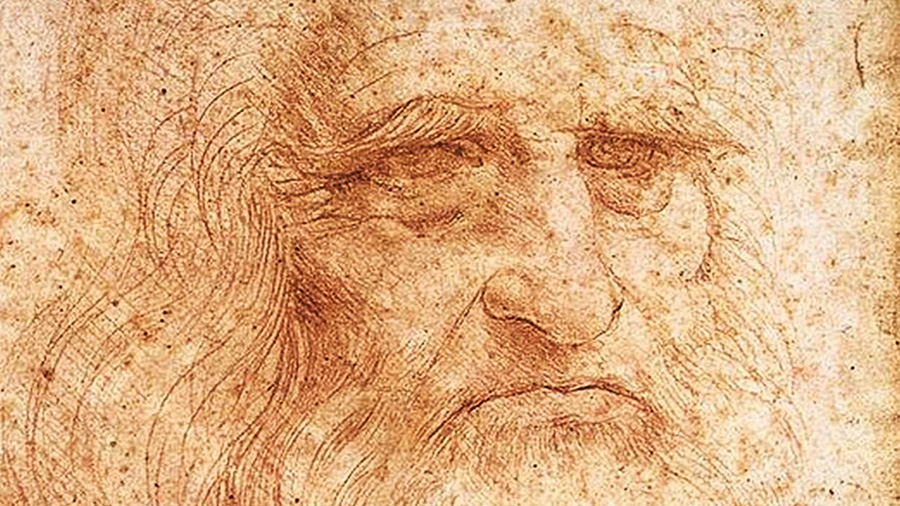

There is a kind of wishful thinking in this game; we claim someone particularly estimable or celebrated as one of ours because, you know, he sort of kind of has to be. Recently, for example, the Italian historian Carlo Vecce claimed in his new book Il sorriso di Caterina, la madre di Leonardo that Leonardo da Vinci’s mother was “was a Circassian Jew born somewhere in the Caucasus, abducted as a teenager and sold as a sex slave several times in Russia, Constantinople, and Venice before finally being freed in Florence at age 15.” Breathlessly reported in publications like Tablet, it would certainly be a feather in our Jewish hats if yet another of the greatest thinkers in history was one of our own! I mean, you can never have enough, amirite?

Of course, even setting aside Vecce’s shoddy scholarship – he is no historian and he makes wild claims based on supposition and speculation that would be at home in Michael Baigent, Richard Leigh, and Henry Lincoln’s The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail or, for that matter, in Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code – there is the matter of what da Vinci’s supposed Jewishness actually amounts to. Even if one accepts the possibility that the Italian master was halakhically and matrilineally Jewish, which is doubtful, is that enough to say that he was really one of us?

Did he live a Jewish life, suffer antisemitic persecution, or stand up for fellow Jews? Is there something particularly Jewish in his notebooks, or in his Uffizi “Annunciation,” or in “The Last Supper?”

We do this a lot with historical figures whom we respect and admire. We are told that Karl Marx’s antisemitic screed “Zur Judenfrage” can’t be antisemitic because, don’t you know, he was Jewish. We crane our necks listening to the oh-so-very Lutheran Die Deutsche Liturgie to hear faint hints of Felix Mendelssohn’s Jewish heritage, handed down by the great philosopher, his grandfather Moses. Sports fans thrill to the fact that British rugby star and LGBTQ rights activist Ben Cohen really plays on our team, and he’s a real mensch to boot!

Only… neither Marx nor Mendelssohn were actually Jewish; their parents were. Heinrich and Henriette Marx converted to Christianity, joined the Prussian state Church and, according Marx biographer Jonathan Sperber, raised young Karl as a thoroughly conventional middle-class German gentile. Abraham and Lea Mendelssohn explicitly rejected their Jewishness and had their son baptized in the Calvinist Reformed Church. For his part, Felix grew up to be an utterly devout Christian who composed masses, motets, oratorios, and other choral works that celebrated his faith and praised his savior.

Despite Cohen’s priestly name, and as much as I would love to claim such a talented athlete and all-around great guy as one of our own, he is quite candid about not being Jewish. “My family’s not Jewish, but a few generations back they used to be,” he told an interviewer. “I think it was my great-grandfather that married a non-Jewish girl and broke with tradition.” I appreciate his honesty and unwillingness to claim an identity that isn’t actually his – we should learn from that.

We need to be careful about these things, at least in part because antisemites invariably turn the equation around and use the fictive or presumed Jewishness of historical and public figures to delegitimize them. “The Jew,” in this antisemitic formulation, is the eternal other that has burrowed into good Christian society like a parasite, to undermine it from the inside. On more that one occasion, I have heard Cohen dismissed as “that queer kike” (although he is neither) in order to discredit his campaign to combat bullying in sports. It is all-too reminiscent of the antisemitic slanders aimed at the Anglican Benjamin Disraeli, Britain’s Liberal prime minister from 1874 to 1880, by his Tory rivals.*

Nor should we forget that the Third Reich denounced Mendelssohn’s compositions as Entartete Musik (decadent music) and banned their performance on the grounds of his supposed Jewishness, or that conservatives, fascists, and totalitarians in America dismiss Marx’s work as the work of a Jew. Not only does that mean that Marxism can be denounced out-of-hand as illegitimate and “un-American” but, for many, it is all the proof they need that it is somehow the philosophical foundation (often as “cultural Marxism”) of an International Jewish Banking Conspiracy that controls global capitalism through the “Davos Clique” and George Soros.

As much as we might want to look longingly at da Vinci, Marx, and others and chant “gabba gabba one of us!” such impulses are never benign. They dilute the real resonances of being Jewish and weaken the bonds of history, of both shared joy and suffering, that bind us together as a coherent community. More malignantly, they reinforce the claims of the antisemites, Christian nationalists, and fascists who want to arrogate Jewish identity as the Mark of Cain that identifies all that is corrupting and evil.

It is one thing to celebrate those great thinkers, athletes, artists, and celebrities who really are part of our communirty but what made Penny Marshall Jewish in the minds of Saturday Night Live’s Knutsens was that she is a loud, obnoxious, urban, ethnic woman who tells jokes – that she conforms to an old, and toxic antisemitic stereotype. Let’s not lend credence to those stereotypes through misplaced ethnic pride.

***

* In fairness, Disraeli, a rather theatrical literary celebrity even for the period, often described himself as a “Judeo-Christian” as a way to claim a certain exotic soulfulness.